By Charles H. Green

Chaos, or said on the other side of the planet, 混乱, is defined as a state of utter confusion or disorder; a total lack of organization or order. Between the withering summer heat, anticipation of a pending Federal Reserve rate hike and the rumbling of the Fall football season, hearing about China’s devaluation of its currency may, in fact, have American bankers, wondering whether we‘re turning back to chaos again, just as expectations for ramping back up to economic normalcy were at hand. It’s a fair question.

What does this news from China mean and how does it affect Main Street lenders?

China’s decision to devalue its currency this week is part of a long effort to be seen as a  major player in financial markets. But the move carries some risk for the world’s economy. Even as the second-biggest economy in the world, China is a powerhouse of trade and manufacturing that yearns to be more. They want prestige in the global financial markets like the United States, Japan and England. That is believed to partially have been behind their efforts earlier this year to establish the Asian Development Bank, which will lend money for regional infrastructure projects.

major player in financial markets. But the move carries some risk for the world’s economy. Even as the second-biggest economy in the world, China is a powerhouse of trade and manufacturing that yearns to be more. They want prestige in the global financial markets like the United States, Japan and England. That is believed to partially have been behind their efforts earlier this year to establish the Asian Development Bank, which will lend money for regional infrastructure projects.

Likewise, their decision earlier this week to let the Renminbi (commonly call the ‘yuan’) to fluctuate more freely is another part of China’s effort to become a financial player on the world stage. Their ultimate ambition is to have China’s currency to be a globally accepted reserve currency, meaning that the yuan would become one of the small, elite group of currencies used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to determine exchange rates.

But the IMF won’t do that as long as the yuan’s value is tightly controlled by the government. So China’s central bank has been pushing the government to let the yuan fluctuate a bit.

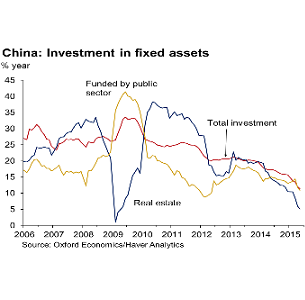

And part of the government does think that by allowing interest rates and currency values to move more freely will help iron out some of the structural problems that now threaten the Chinese economy, and which have led to slower growth than targeted. And as such, the high levels of debt that have accumulated domestically cloud the intermediate horizon.

China has eased the value of the yuan about four percent against the dollar, which is very good for the Chinese economy, but not so good for the U.S. or the rest of the world’s economy. When the yuan loses value, Chinese goods become less expensive to import, which makes it harder for companies in other countries to compete to sell goods–their imports become more expensive and Chinese goods are more competitive.

To be sure, a lot of China’s trading partners may be tempted to devalue their own currencies, which theoretically could end up causing countries to compete with each other to see who can drive their exchange rates down the most. That would bring more instability to the world’s economy at a time when most regions are still struggling to recover.

Moving China toward an open market economy

According to coverage by the NYTimes, the timetable set by the Peoples Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank, is year-end to open up the country’s markets, and as the year passes, questions are emerging about whether their creaking financial system, and the people who run it, are up to the task. Allowing market forces to assert more influence over the exchange rate, as demonstrated this week, is only one step on the road to tearing down the barriers that keep money from flowing across China’s borders.

While President Xi Jinping has promoted the idea of market forces playing a decisive role in China’s economic priorities, the PBOC has led the push to liberalize capital markets.

But China’s stock market meltdown exposed significant holes in the country’s financial regulations that regulators are now trying to plug. That leaves political leaders and the technocrats who run the government with little capacity or appetite to oversee a system where investors worldwide have the ability to easily move money in and out of China.

According to economist and NYTimes columnist Paul Krugman, “China is ruled by a party that calls itself Communist, but its economic reality is one of rapacious crony capitalism. Yet their zigzagging policies over the past few months have been worrying. Is it possible that after all these years Beijing still doesn’t get how this “markets” thing works?”

China’s economy is “wildly unbalanced,” with a very low share of GDP devoted to consumption and a very high share devoted to investment. This imbalance was sustainable so long as the country was able to maintain extremely rapid growth; but that growth has inevitably slowed, as China’s labor surplus dwindled. As a result, returns on investment are dropping fast.

Continued Krugman, “The solution is to invest less and consume more. But getting there will take reforms that distribute the fruits of growth more widely and provide families with greater security. And while China has taken some steps in that direction, there’s still a long way to go.”

Ripple effects that may be felt on Main Street

To travel to Beijing from the American midland is about a thirteen hour flight. Given that the average airspeed on those flights are around 500 mph, you can figure out that it’s another world away, right? So why does a currency devaluation there have anything to do with a small business in Southern Illinois, Florida or New Mexico? That would be because we are all connected–at least through the global economy.

China is one of the world’s largest buyers of petroleum and many other commodities. A massive infrastructure building program and serving the biggest population on the globe requires lots of materials, as it does to churn out a broad assortment of manufactured goods for the planet.

It’s no coincidence that U. S. oil prices slid to a more-than six-year low Friday on escalating concerns about the mismatch between global supply and demand. The WSJ reported that oil futures on the New York Mercantile Exchange hit a low of $41.35 a barrel, a level seen last on March 4, 2009, when the U.S. economy was still mired in a deep recession. Oil was recently trading at $41.88 a barrel, down 0.7% from Thursday’s settlement.

This problem is not solely due to China’s devaluation of the yuan, but is mainly caused by the rapid growth of U.S. domestic oil production, thanks to fracking technology, and the OPEC cartel’s decision to maintain full production in the face of lowering global demand. And now investors are worried about China’s oil demand following its surprise currency devaluation. A weaker yuan makes imports of dollar-priced commodities, such as crude, more expensive.

For America’s Main Street businesses and their lenders, the immediate impact will be felt depending exactly on what their business they’re in (or who they lend to). For companies dependent on importing Chinese manufactured goods, or who can substitute these goods for what they purchase today, the lower currency is an improvement. But if companies are competing against Chinese goods, this move is bad.

Likewise for anyone whose business relies on petroleum or other raw commodities, or similarly concerned about our low inflation rate and the risk of slipping back toward deflation, this move is a concern. The rising tension scenario that turns into anything resembling a competition among global currencies toward steep devaluations turned into a full scale currency war should keep everyone awake at night.

Moving on

China’s currency stabilized on Friday, ending a three-day plunge that shook markets globally amid the Renminbi’s steepest devaluation in decades, as the PBOC set the official exchange rate higher — though only slightly — against the dollar, for the first time since Tuesday.

As reported by the NYTimes, the Renminbi responded by strengthening 0.1 percent, ending the week at 6.392 per dollar. Still, that meant the Chinese central bank had effectively devalued the currency by 4.4 percent over the course of the week, the steepest drop since the country’s modern exchange rate system was set up in 1994.

The sudden decline added fuel to a global debate about currency wars. It also raised new concerns about whether Chinese leaders could manage the country’s huge, but the slowing economy as they pursue a market-driven overhaul to their financial system, which remains broadly under state control.

For years, China looked like the principled non-combatant. As other countries sought to secure an economic advantage by letting the value of their currencies slide on international markets, China held firm on the value of its money. But by sharply devaluing its currency this week, China jumped into the fray.

The abrupt move opens a new phase in what some analysts see as a long-raging global currency war, a development that could leave the United States exposed and undermine efforts to pull the world economy out of the doldrums.

The yen, the euro and several other major currencies have fallen in recent years against the dollar as the Federal Reserve has cut back its stimulus and policy makers elsewhere have sought to obtain gains for their sluggish national economies.

China’s stock markets are still struggling after a sell-off that started in mid-June. The government took extraordinary measures to support share prices, including barring major shareholders from selling stocks and ordering state agencies to buy, with backing from state banks. But they had little lasting effect.

There’s a couple informative charts offered by the NYTimes that track China’s corresponding currency and equity market, which illuminate the effects of their latest policy moves here.

Geopolitical considerations

All of this comes with the backdrop of rising regional tensions in East Asia, largely stoked by a more intentional Chinese assertion of aggressive behavior. The Economist reports that in early in September, President Xi Jinping will take the salute at a military parade in Beijing, his first public appearance at such a display of missiles, tanks and goose-stepping troops.

Officially the event will be about commemorating the end of WWII in 1945 and remembering the 15 million Chinese who died in the Japanese invasion and occupation of China of from 1937-45, suffering more lost people than any other country except the Soviet Union.

But next month’s parade is not just about remembrance; it’s about the future, too. It will be the first time that China is commemorating the war with a military show, rather than with solemn ceremony. The symbolism will not be lost on its neighbors and will unsettle them, because China, today’s rising, disruptive, undemocratic power is no longer a string of islands presided over by a god-emperor.

Instead it’s the world’s most populous nation, led by a man whose vision for the future (a richer country with a stronger military arm) sounds a bit like one of Japan’s early imperial slogans.

And now what?

It remains to be seen what will happen in the next few days and weeks, but just about as universal consensus agreed that the Federal Reserve was likely to announce an interest rate hike at the September meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), there is pause to consider the possibility of another delay. No one, probably including the voting members of the FOMC know how the Fed will respond.

China has been on their watch list for some time due to concerns about the slowing of their GDP and recent stock market fluctuations, which have given U.S. policy makers a substantial reason to hesitate. Given other concerning trends, like lagging U.S. consumer spending in the face of significant reductions in gasoline prices, might cause the FOMC to once again leave 0% interest rates in place.

What should commercial lenders do to respond to these changes or possible threats that these events represent? Think about how the economic horizon might affect the particular industry of companies in your portfolio, and carefully monitor those who may be vulnerable. Screen new loan applications that are exposed to more competitive imports from China, or involved in the manufacture or distribution of the commodities that are suddenly falling in price.

Most of all, keep your eyes on more news ahead to stay ahead of changes that impact your existing book of business and the loan volume in your budget.

Did you know SBFI offers commercial lender training–learn more here.

Read more stories of interest to commercial lenders here.

What do you think about this story? Comment below or write me at .